A liturgy of surprise...

Virginia Wolff says that “A good book is never finished - it goes on whispering to you from the wall.” In my experience, some books whisper with such frequency and fervent intensity, that I've had to give up on the idea of them ever residing on the wall.

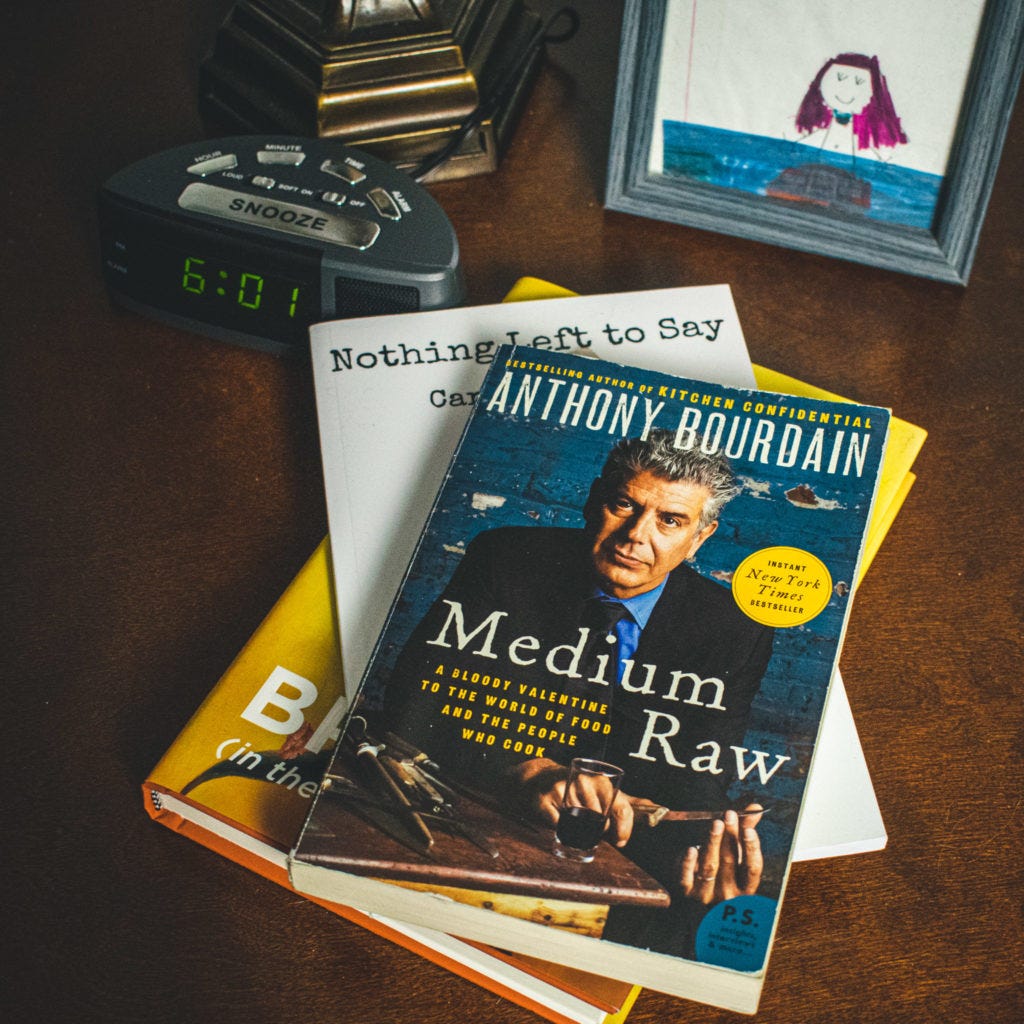

I keep a copy of Anthony Bourdain's book, Medium Raw, on the night stand beside my bed, as if it were a copy of Bible. It's a ludicrous thing to say and do, I know. It's absurd to even suggest that Bourdain's book and the Bible are on equal footing.

Throughout my academic pursuits in the realms of religion and the Humanities, I have devoted myself to researching the sacred text, and I can say with a great degree of certainty that, to my knowledge, none of the biblical writers have ever had lunch with Iggy pop, or eaten spicy Pho on a Vietnam street corner, a scene that Bourdain, himself, describes as "the landscape of human desire...strewn with the spent expressions of human lust". Clearly, Bourdain has a far deeper and richer understanding of the multifarious complexities within the human condition.

I've learned a lot from my time spent studying the Judeo-Christian canon, but no one has taught me more about faith, belief, and belonging than St. Anthony of Bourdain, patron saint of fucks not given. It seems that Moses and the apostles, will simply have to settle for second place.

Early on in the book Bourdain recounts having one of the best and most exclusive meals of his life, sitting amongst the who's who of the cooking world, "the gods of food", and wondering to himself "what the fuck am I doing here?" As he looked around the room he readily recognized that he "was the peer of no man or woman at this table". He could clearly acknowledge that at no point in his cooking career would any of them have ever hired him. He had found a place at this most prestigious of tables, but he knew it had nothing to do with his talent as a chef.

And yet, it was also abundantly clear that his failure as a cook was intricately intertwined with his arrival at this table. He writes that:

From this rather luxurious vantage, the air still redolent with endangered species and fine wine, sitting in a private dining room...I realize that one thing led directly to the other. Had I not taken a dead-end dishwashing job while on summer vacation, I would not have become a cook. Had I not become a cook, I would never have become a chef. Had I not become a chef, I never would have been able to fuck up so spectacularly. Had I not known what it was like to fuck up - really fuck up - and spend years cooking brunches in bullshit no-star joints around town, that obnoxious but wildly successful memoir I wrote wouldn't have been half as interesting.

He was a chef who garnered acclaim not for his culinary capabilities, but for his writing, and he knew it. Somewhere in his failed attempt to be a worthwhile chef, somewhere in the anxious discomfort of the search, he became something else, something fearfully and wonderfully made.

I'm having a similar dining room realization, though mine is laced with more anxiousness than appreciation. I used to be the youngest person at the table, but not at this one, not today. Tonight, at this table, I'm everyone's senior by a few years. I'm not sure when the shift happened exactly. Like the way most things change, I'm certain that it transpired quietly and in plain sight. And, in my case, I'm convinced the slow discretion of the change was made all the more imperceptible by the fact that, over the past few years, I have taken great strides to stay hidden from communal tables of almost any and every kind.

My vantage is not particularly luxurious. The table I'm sitting at is not in an exclusive, private dining room. I am not amongst the elite or the who's who. In fact, most of the people here I'm meeting for the first, and quite possibly the last, time. It's just a casual dinner at a beachside bar, celebrating the accomplishment of a friend of a friend, but I still feel like I'm the peer of no man or woman here. I look around the table and I am greeted by youthful faces; vibrant with vigor and vitality, glowing with the fervency of all that they have already accomplished, and alive with all they still hope to, and probably will. There is welcoming in their eyes, but I find none of the weighted fatigue that must be so readily obvious in my own.

I work hard to hide the wear and tear of my dogged miles, but I feel so exposed. Like a car broken down in the middle of the road, smoke billowing from underneath the hood, hazard lights flashing; my mere presence is a spectacle.

Chuck Palahniuk says that "maybe you don't go to hell for the things you do. Maybe you go to hell for the things you don't do." and, at this moment, I sense how incredulous salvation is when one is so obviously damned. A lifetime of regret and incapacity, arriving in an instant, I all too clearly come to understand eternal torment.

As the only child of a minister, I spent far more time around adults than I ever did around kids my own age. If I wanted to be seen and heard, if I wanted connection, community, and comradery I was going to have to make a space for myself at the grown-ups' table. This meant that I had to learn to be articulate and intelligent, I had to be knowledgeable and outspoken. I had to be driven and ambitious. I had to learn to hold my own and I did, my whole life, until I didn't, until I couldn't.

I reached. I clawed. I pushed. I pulled. I climbed up that damn water spout, and I made something of myself, or I started to anyway. But then down came the rains, they were ceaseless and unrelenting, and they washed me completely out.

Amidst the torrential downpour of life at its bleakest, its easy to believe that even the sun has lost hope and abandoned the day. But, the sun does, indeed, come back. Sometimes it just doesn't stay out for long. And, sometimes it doesn't dry up all the rain, at least not all at once.

If someone would have told me at age 13 that I was five years away from meeting the woman I was going to marry, I couldn't have fathomed it, or even thought it possible.

If someone would have told me at 18 that I was just three years away from experiencing one of the most profound forms of life-altering love when my son was born in a Cape Canaveral delivery room, I would have, at best, only patronizingly smiled.

It goes without saying that there's no way in hell I would have believed them if they told me that I was only a little over two years away from experiencing it yet again at the birth of my daughter.

And if someone would have told me that five years after that, I'd suffer through two devastating layoffs, lose almost everything I'd spent the past nine years working to achieve, and only moderately recover after another five years; the sheer horror would have surely made me hope that it was a lie.

But, perhaps, the icing on the cake of existential angst would be if someone would have told me that at the beginning of 2020 the contents of an entire life would be neatly and catastrophically condensed down to 6 cardboard boxes and a duffle bag, desperately packed into the back hatch of a 2004 Ford Expedition after the devastating end of a nearly 15 year-long marriage.

And yet here I am, still reeling, still recovering, still wondering what "normal" might mean now. Seth Godin explains that "Every normal is a new normal, until it is replaced by another one". But, a 'new normal', almost never feels normal, not at first anyway. Sometimes it just feels fucked-up; really, really, fucked-up.

So much of my life has felt like one unfolding fuck-up after another, and then, one day, something shifts, something changes, something happens and all at once, somehow, it feels like it all makes sense. In one seemingly serendipitous moment, in the warm auburn glow of the otherly and the unexpected, we realize that this crooked path has been twisting fast towards the clearest of all possible views.

John Green says that "You can't see the future coming - not the terrors, for sure, but you also can't see the wonders that are coming, the moments of light-soaked joy that await each of us." Maybe that's part of the excitement of sitting with such a limited scope. We know there's something wild and ferocious taking place so near and yet so unavoidably outside of sight, somewhere just beyond what we can see. We can hear a faint yet unmistakable roaring in the distance. We can feel the rumble of something rushing towards us, but we just can't see around every curve, or every corner, if we can ever see around any of them at all.

Sometimes, it's not so much the terror and trauma that we suffer from, but rather the fear and the anxiety of our unknowing, near-sightedness. Sometimes we struggle with despair about what has passed us by and all our doubts about what's on the verge of arriving, because what we're really struggling with is only the misunderstandings of our partial vision.

Maybe there are no mistakes. Maybe, nothing is ever fucked up; not really. What if, as Palahniuk presses us to ask, everything has been "unfolding in perfect order to deliver us to a distant joy we can't conceive of at this time"?

We are always in the thick our stories. We are never privy to the whole picture. Perhaps, what appears as a mistake so closeup is actually the thing that brings us precisely to where we most direly need to be, and if we could just, for a moment, pan out into a wider perspective, then we would see it.

If we did, and if we could, we would see that unbeknownst to our own limited view we have been inaugurating a liturgy of reverent surprise right under our own noses all along. We would see that every persistent step taken with both steadfastness and uncertainty has been quietly shifting the world into the shape of our own consolation. We would see that we have been building a temple this entire time; a sanctuary of ultimate concern formed and fashioned by the sacred steadiness of our striding through the foreboding uneasiness of the unseen. We would see that we were always on our way home.